History of anesthesia or pain control (I). The discovery of Narkosis

1991/05/01 Loizate, Alberto Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

The century of modern surgery began on October 16, 1846 at the Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. That day, with Morton and operated by the prestigious surgeon Warren (in front of a group of well-known doctors), the first painless operation was performed by administering ether gas to the patient. The cheek tumor was removed from the cheek to the patient who did not even develop pain.

Holmes, a professor of anatomy and literature enthusiast at Massachusetts General Hospital, chose the name anesthesia to designate who he had just found. That year was born the narcosis or general anesthesia that is obtained from chemicals.

Jürgen Thorwald, H was present at this event. Based on the manuscripts of his grandfather, St. Hartmann, he states that the current person cannot resemble the great step that took place that day.

Before this date, surgery was terrible and terrible, and surgeons had to be hard people, getting used to the pains and screams of the sick in order to carry out their work. H. According to St. Hartmann, he was present a few days before the operation of October 16, saw the removal of the tongue of a cancer patient, and at the same time that the incandescent iron touched the hill of the tongue, the patient died in shock in a cry of pain. Days later, says Jürgen Thorwald, under Warren's scalpel, I saw a quiet young man, without screams and without stopping, away from the mines beyond all the measures that the previous ones had to endure.

Thus began the new era of surgery, and like many other discoveries, we could say that this was to some extent unforeseen.

The pre-narcosis history is the pre-history of surgery. The surgeon's ability was limited by the unbearable pain in all surgical operations. Pushed by the ghost of pain, the best friend of the speed of surgeons then. If things had to be done (and this often happened in wars and accidents) for pain and blood loss, operations had to be rapid. Surgeons had great skill. For example, the cut of the leg (typical operation of the war and with current advances, but more than half an hour) was carried out about two hundred years ago in three or four minutes, and that's what it had to do if the patient came alive.

The prestigious surgeon Bertrand Gosset said: Surgery is a history of the last hundred years that begins in 1846 with the discovery of narcosis, that is, with the possibility of operating without pain. All the above to this date is but the night of ignorance; the temptation of pain and darkness. However, in the last hundred years history offers the greatest vision that humanity knows.

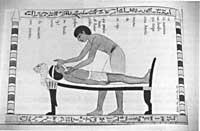

To go to the surgeon, the patient had to be desperate for pain, and surgeons used hypnosis, a lot of alcohol, cold effect, nervous pressure, or herbal teas, usually with scarce consequences. The most useful means was to tie the patient to his seat or bed.

Next we will explain the steps taken to find narcosis. To find the first traces, XVI. We have to go until the 19th century. Around 1540, Paracelsus, a Swiss physician and alchemist, donated to the chickens a sweet vitriol oil (baptized by another alchemist as aeter a few years earlier) mixed with food, and discovered that the hen was sleeping temporarily. Paracelsus fought for classical medicine and defended that, against the theory of universal treatment he proposed, each disease needed special treatment.

XVII. In the twentieth century the evolution of blood circulation was known thanks to the works of Miguel Servet and William Harvey. XVIII. In the twentieth century the respiratory function and the need for oxygen to maintain life were known.

In 1800, the English chemist Humphry Davy attributed to the pain of his authority the inhalation of nitrous oxide or barrier gas discovered in 1774, with a special feeling of pleasure. Davy also published an article. He said nitrous oxide, apparently capable of eliminating physical pain at high doses, could be used in interventions where there is no significant loss of blood. The idea of Davy was not received by anyone and neither did he go deeper.

Decades later, in 1823, a young English physician began testing animals due to the unbearable painful burden of his patients in surgical operations. To do this, he introduced the animals into the glass hood and then introduced carbon dioxide (CO 2). In this way the animals lost consciousness and it was possible to cut the ears or tail without signs of pain. But the risk of death from poisoning was high with carbon dioxide and had to rule out the idea of demonstrating it in humans. From there to use other gases, but Hickmann did not.

Today we know if the Crawford W, doctor from Georgia. Long, in 1842, breathed the ether several times painlessly into his patients for small interventions. The idea of ether was given by a patient of his, James Venerable, who had to be operated often by neck tumors. Venerable and other young people formed parties and, instead of getting drunk with alcohol, they got drunk with etarras. Dr. Long drank a lot of alcohol to reassure his patients and, like Venerable, it occurred to him that it was more comfortable to give him ether than conventional alcohol. And although the results were good, he did not realize that was a great discovery.

A couple of years later, Dr. Smile of New Hampshire, a priest who suffered terrible cough attacks, for not being able to remove them optionally, gave him a mixture of ether and opium to breathe and the priest fell unconscious. Then it gives the same confusion, had to open the abscess (pus or accumulation of passes inside the body) and saw that the operation was done without pain. This doctor wanted to continue investigating, but his colleagues stressed that opium (used for thousands of years) was only administered in deadly doses of anesthesia. And congratulating him that his essays had no more regrettable end, they advised him not to use it more times. Smile did not realize the anesthetic property of the ether. For him it was a mere opium solvent.

Horace Wells, a dentist in a small American town, was the real discoverer of narcosis, despite not believing in the first test he did before other doctors to prove. As we said before in ether, nitrous oxide or ridiculous gas was a toy for people at fairs and parties.

Horace Wells read in 1844 in his local newspaper the following announcement: Today in Union Hall, spectacle of phenomena that occur breathing nitrogen prooxide or commonly known as barrier gas. For viewers who want to try, 40 gallons of gas are available. According to the nature of the people who breathe, they sing, laugh or fight. For the exhibition to be serious, only respectful men will be allowed to breathe gas. Price 25 cents.

Wells, at age 29, was a well-known village dentist and yet visited the street show of laughter gas. Being of those who have to try everything, he breathed the gas and when he woke up after a kind of drunk (like many other laughs, singing and jumping) he returned to the spectators' place. After breathing the gas like him, a man jumping on stage saw a blow against a chair in the leg, in the tibia. Wells also noticed the noise of the blow and seemed to him to break the bone, but instead of screaming in pain, he continued to laugh and dance.

Then Wells began to think about the usefulness of the gas and did not take away the eye of those who beat it. He, like Wells, at the end of the drunkenness, quietly left the stage to his seat. Wells got up and next to him asked if hitting the chair had hurt his leg. He suffered no blow. Wells received a pant and a bloody wound appeared on the leg, a big wound.

Wells then did not live for his discovery. Being able to die breathing enough to fall asleep for the sick, he made the first test with himself and told a companion to remove the tooth that was corrupt. It was the first narcosis session in the world. After breathing more gases than anyone else, and with the safety that circulated in the limits of death, the white color of his face became purple blue. The eyes remained ready and still, deep asleep. His companion surprised him painlessly.

Before being exhibited in Massachusetts, she used 14 or 15 times nitrogen prooxide or sweeping gas, and achieved great fame for pain-free operations in the village she lived in. But he wanted to show his discovery to the believing world of scientists, and for that he went to Massachusetts (to show it before official science) in search of the opportunity that cost him so much. For this he had to use all his skills, because they did not believe him. Also at the time of his presentation, he was given an ironic welcome.

In 1845, Wells, at the Massachusetts General Hospital, exposed to a prestigious physician, student, and team of monitors (although the ears did not believe it) who knew the method of performing painless oral operations. To prove his discovery he asked if any tooth had to be removed. A pupil showed his affected tooth. Wells told him to put it and put a rubber ball in his mouth. He opened a wooden txotx and asked the patient to breathe deeply.

After three or four breaths, while something was pronounced and the color of the face blushed, he fell asleep. Wells threw the tooth extraction device into his mouth and with the first jerk the patient did not shoot the pains that everyone expected. But in the next jerk, the patient began to scream and what initially died among the public, later became laughter and the dentist retired with shame. The patient, despite shouting, said after that he did not remember what happened.

Wells showed well the method in the consultation of his house, perhaps because of the nervousness of the trance he suffered some error and he mistakenly. That's why viewers pretended to be a funny joke. At that time, among doctors and surgeons, it was dogma that surgical acts were related to pain. In addition, the galenic concept of the disease persisted. The disease was an imbalance between blood, phlegm, bile and black bile, four humors of the body. As a result, he proposed common and general remedies for all diseases: purges, bleeds, patches and counteracts. This theory was a major obstacle to the progress of medicine.

After that error, Wells' name went out until he was recovered by medical historians. His comrade Morton succeeded Wells with ether gas a year later (1846).

The discovery is based on the new American world and soon passes to the old Europe that considered it a treasure of knowledge; to the prestigious Hospitals of London, Paris and Edinburgh. Until 1900 anesthesia did not become a specialty. Surgeons were both anesthesiologists and surgeons. The fact that it occurs in North America may be due to its precursor status and the absence of strong medical authority. In Europe there was a powerful medical hierarchy in which revolutionary therapies could not be accepted.

Then they discovered new types of narcosis gas, and so, a hundred years later, we have come to this day. Today operating with narcosis has become so common that we don't think it can be otherwise. But painless operation has its risks. These risks were first described by anesthesiologist Snow in 1958. Until then it was considered that the anesthesia itself was not harmful, or rather that the substances used for anesthesia did not cause death and that those that produced death were human errors in use.

The substances used in anesthesia affect many systems and organs. They decrease the functioning of the respiratory system, decrease the blood circulation of the heart and increase the risk of heart attack, raise blood pressure and damage the liver in high doses. The risk of death from anesthesia is directly related to the patient's preanesthetic health status. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the risk of anesthesia and according to what can be extracted from the different studies carried out, regardless of the health status of the patients and the type of general anesthesia, the average risk of mortality would be one in every 1,600 interventions.

But this risk of death, in good health and without major surgical intervention, is reduced to 1/10,000. On the contrary, if the subject to general anesthesia is a person with advanced cardiac disability, the risk rises to 1/50. But as in all the statistics, when applying them to a specific patient we cannot know for sure what is going to happen in that case and therefore, for the patient and his family to understand, would compare the operation with a car trip. We know it is in danger, but we are still.

At present there are many means of patient control during anesthesia and the patient is monitored at all times by anesthesia. Their constants remain always controlled, there are special places to wake up, and it can be said that deaths are almost always accidental.

Currently, by means of general anesthesia, along with the removal of pain to the patient, the necessary muscle relaxation is achieved. By getting relaxation of all muscles of the body through relaxing substances, breathing is also done with muscle movement, so the patient's lungs should connect to an artificial respirator. This is achieved by a special tube that enters the windpipe through the mouth. The usual steps in general anesthesia are:

- Premedication. Analgesics and neuroleptics are usually given before taking the patient to the operating room.

- Subsequently, by barbiturates inserted into the vein in the operating room, induction is performed and the patient is asleep.

- Then they introduce relaxants into the vein, which make breathing stop. Then the tube is inserted from the throat to the trachea to maintain the oxygenation of the patient.

- In artificial respiration, oxygen may be accompanied by different gases to maintain anesthesia, although the maintenance of anesthesia can also be achieved with substances introduced into the vein.

Jürgen Thorwald wrote in 1956 "The Century of the Operating Rooms" and "The Success of Surgery", using for this purpose the manuscripts left to him by his surgical grandfather. His grandfather H. St. Hartmann was a surgeon who, after being present at the first narcosis in 1846, followed the development of surgery around the world. With money, instead of working in his craft, he tried to know closely the advances of surgery and joined well-known surgeons of his time, collecting in his writings what he saw. Then his nephew Jürgen Thorwald, with the immense material of his grandfather, wrote the two books mentioned.

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia