Ara Hovanessian: all HIV strains use the same key to enter the cell

2005/05/01 Galarraga Aiestaran, Ana - Elhuyar Zientzia Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

all the questions we asked him. Certainly, we wish you to advance on your way.

The AIDS virus has been identified for twenty years and the vaccine has not yet been achieved. Why is it so difficult?

There are two main reasons. On the one hand, HIV is a virus but retrovirus type. This means that it integrates its genetic information into the genome of the cell that infects it. This is essential for reproduction and, incidentally, is integrated into the human genome that infects its genetic information.

Somehow, it becomes part of the human being who infects the virus. Consequently, it is very difficult to destroy the virus without damaging the body cells.

It is different from other viruses. For example, the influenza virus that causes the flu is well known. This also infects cells in the body and uses them to reproduce, but is not identified with the genome of cells. It is a host in the body of the one who infects.

So, one of the causes that makes getting the vaccine difficult is that it becomes part of the human being who infects the virus. What is the other?

The other is that HIV is constantly changing. The last variant is the one that has managed to survive, which means a greater capacity of cell infection than the other. Therefore, with each change, the virus becomes increasingly aggressive. This is very important for the virus. And is that our body is programmed to protect us from attacks, for that has its immune system. The immune system first detects the aggressor and then destroys it. But if he does not know the aggressor, he cannot detect or destroy it. The constant change in HIV makes the immune system unable to know it. This is the HIV strategy. That is why it is so difficult to get vaccinated.

Other viruses also suffer mutations. For example, the influenza virus also changes, so they have to get vaccinated every year. But it doesn't change again and again or for every person who infects it. The influenza virus has the same genetic information after infecting a person and infects his companion unchanged. Thanks to this, from the identification of the variant in which the year is located, researchers vaccinate and at least that year have the ability to protect themselves from the flu.

What characteristics should the AIDS vaccine have?

An effective vaccine should work on two aspects of the immune system: on the one hand, it should be able to promote the synthesis of anti-HIV cells, T-lymphocytes. On the other hand, it should help the immune system create antibodies that neutralize the virus.

Twenty vaccines are currently being tested, but all of them work only in the first part. Few or more, all are able to promote a response using T lymphocytes. However, so far no one has gotten a vaccine that causes antibodies. In that sense they have become pawns.

In fact, you are working in that area, in the antibody response, are you not?

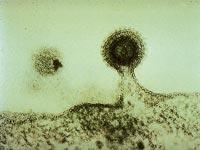

That is. Actually, the initial intention was not that, but to understand how the virus is introduced into the cell. When analyzed, it has been proven that by infecting human CD4+T lymphocytes, HIV is associated with the cell by a glycoprotein in the skin: gp 41. Specifically, the connection of the plasma cabin of the lymphocyte to the protein zone is made by the CDB-1 part. The name of the CDB-1 peptide indicates: Caveolin-1 Binding Domain. This allows HIV to associate, merge and cross the plasma membrane of the lymphocyte. In short, this way it manages to infect the cell.

For we have realized that the CDB-1 peptide never changes. Being the key to entering the lymphocyte, it cannot change its appearance, otherwise it would not enter the lock and could not infect the cell. Therefore, all variants of HIV have the same key.

Then we wanted to know if antibodies against the CBD-1 peptide are produced. To do this, a synthetic peptide has been injected into rabbits. And we have seen that synthetic peptide causes an antibody response in rabbits.

Therefore, I have to recognize that we have been fortunate, first to find the key and then because we have verified that rabbits generate antibodies against it. In addition, when we have tested the effectiveness of antibodies in human cell cultures, we have obtained really satisfactory results.

And do you think that, as in rabbits, synthetic peptide injection in humans will generate antibodies that prevent infection?

Yes. In general, antibody response is similar in laboratory and human animals. That is why these tests are carried out in animals, first in rabbits and then in macaques. The last step is to test in humans. However, it may be thought that if antibodies against peptide have been created in rabbits, they will also be created in humans.

In human cell cultures we have shown that antibodies are capable of neutralizing several GIB-1 strains. This type is the most widespread and there are many strains, but as everyone has the same key, the antibody affects everyone. In fact, antibodies bind to the key, thus preventing the fusion of HIV with the cell.

In addition, antibodies act on the other hand, eliminating already infected cells and thus avoiding the proliferation and spread of the virus.

But if this synthetic peptide is capable of producing an immune response, why don't antibodies be generated against it when the peptide is part of the virus's surface protein?

HIV is rare in the human body and its proteins are foreign, so man's immune system responds against these foreign proteins. It produces many antibodies against many HIV proteins, but all of them are not essential. Against the key peptide it does not generate antibodies. Why? Because the virus, not losing the ability to infect, hides that part. We

have seen antibodies against peptide in 1 or 2% of those infected, but it is not usual. This allows the use of synthetic peptide as a therapeutic vaccine, that is, not only to prevent infection, but also to cure it. In fact, soon we will begin to test the peptide for therapeutic purposes.

However, for preventive use, time increases. We will try it in the first pots and if everything goes well, we will have to ask permission to try in humans. However, for the AIDS vaccine, the peptide we have synthesized would be just an ingredient. In addition, a component that promotes the cellular response of the immune system should be provided.

From the economic point of view, making peptide will not be expensive, right? That is, will the price not prevent vaccination and distribution?

No. Synthesizing peptides is not cheap, but neither expensive. Other vaccines contain biological material and are expensive: they are difficult to make and even preserve. However, peptide processing is simpler and large amounts can be made, not so expensive. Therefore, the price will not be an obstacle to vaccination.