Early detection programs for breast cancer: benefit and damage assessment

2013/09/01 Irizabal Esponda, Juan Carlos - Sendagile kliniko nagusia, Erradiodiagnostiko ZerbitzuaOnkologikoa Fundazioa Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

The effectiveness of screening programs was first evaluated in 8 randomized trials conducted in Sweden, Scotland, New York and Canada between 1963 and 1982. The meta-analysis showed that mortality decreased by 30% among women aged 50-74 years.

In 2002, the International Agency for Cancer Research agreed, based on the review of the published evidence, that mammographic screening is effective in reducing breast cancer mortality.

In December 2003, the European Council recommended screening mammograms to member states. Based on these bases, the European States have launched their programmes.

In 2007, 54 million European Union women (50-69 years) were abducted from breast cancer in the 22 member states that approved these policies.

Now that screening is widespread, several types of studies will become major studies that will report the influence of breast cancer screening on the population.

Situation in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country

Breast cancer remains the most common cancer among women (26.2% and 26.5% of women's cancers in the Basque Country in 2008 and 2009).

Its influence has grown significantly, especially in the second half of the 90's, since the start of population screening.

The number of cases diagnosed annually has increased from 687 to 1,226 in the period 1986-2006, although the increase is lower in rates reached by ages.

Women with breast cancer score 19.5 points: In the period 1986-1989 it was 67.9% and its five-year survival has become 87.4% in the period 2000-2004.

Significant decrease in mortality: 26 out of 100,000 women in 1992 and 17.6 in 2008.

Since the implementation of the Early Detection Program, conservative surgical treatment has increased, from 43% of women outside the program to 72% of women in the same.

These changes are related to early diagnosis and improvements in treatments.

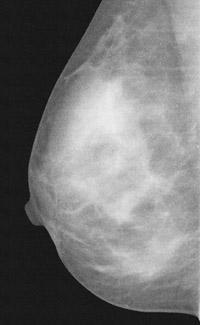

A bilateral mammogram (two projections: semi-lateral and cranial transverse) is performed every two years in the screening test.

Home: November 1995 in Alava and Alto Deba, expanding in 1997 to the rest of the ACBC.

Initially all women of the ACBC between 50 and 64 years old. In 2006, the program was extended to women up to 69 years of age. In 2011, women aged 40 to 49 with a family history of breast cancer were approved for enlargement.

Information to women regarding the decision to raise

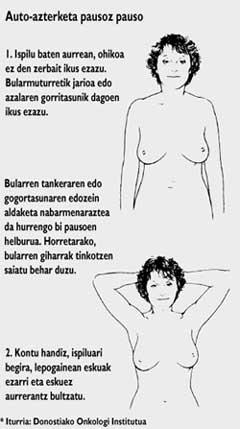

The woman participating in the screening program should know the benefits of the test and the damages and limitations.

The benefits are often known and one of them is early detection of breast cancer before symptoms appear. In this way, treatment can be started prematurely, reducing the need for aggressive treatments (surgical, chemotherapy and radiation therapy) and prolonging survival, decreasing breast cancer mortality.

The damages are listed in order of importance and are: overdiagnosis, false positives and X-ray exposure.

· Overdiagnosis (or number of excessive diagnoses). Not all breast cancers diagnosed by screening are aggressive. If the mammogram is not performed, some cases will have no symptoms. However, these cancer cases cannot be separated from diagnosis or treatment if they are lethal. The information available to predict the evolution and aggressiveness of breast tumors is very scarce, especially in the case of carcinoma in situ. It is necessary to know better the indicators of tumor evolution, thus reducing the burden of treatment.

Therefore, if we currently want to reduce breast cancer mortality, we must pass a cancer overdiagnosis rate and therefore an unnecessary treatment rate.

· False positives. These are abnormalities detected in mammograms that require non-invasive complementary studies (other mammographic projections, ultrasound and/or MRI) or invasive studies (biopsy). The end result is that the changes are benign and not breast cancer.

· Risks of X-ray exposure. In mammograms, radiation exposure is very low.

A recent study estimates that the risk of radiation breast cancer is 1 in 1,000 women tested throughout the screening period.

Among women, 1 in 10 women are at risk for breast cancer throughout their lives. In practice, the decision to perform a mammogram increases the risk of breast cancer by only 0.1%.

Limits include false negatives, intermediate cancers, and second appointments.

· False negatives. In these cases, despite breast cancer, alterations are not seen in mammography.

False negatives are determined by the limits of the mammographic study itself: women should know that a significant percentage of cancers can remain undetected, especially among women who are in the premenopausal phase and those who have breasts (high-density breasts) with a high content of fibroclandular tissue. These women, in fact, have a higher risk of breast cancer.

It should be noted that the sensitivity of mammograms is not as high as indicated in the first screening recommendations, when it was considered between 85-95%. The real sensitivity range of mammography is wider, between 68 and 95%, and may be lower in high-density breasts.

· Intermediate cancer. These are cancers diagnosed between screening mammograms.

· Second appointments. Another drawback of screening is that the radiologist does not read the mammogram at the time it is done, so a second appointment is given to some women to complete the study.

High rates for a new appointment increase program costs and cause unnecessary anxiety for women (false positives). However, when the rate of the second appointment is low, the detection rate decreases and the cancer rises.

Debate

In Public Health, the validity of breast cancer screening programs in healthy women is continuously debated.

The debate has intensified with a study conducted between 1986 and 2008 ("Retrospective Descriptive Analysis of Mortality Trends") among American women over 40 years of age since its publication in 2012 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The conclusions of this study raised great uncertainties about the value of screening mammograms, indicating that their incidence in the decrease in mortality is low and that the number of overdiagnoses is high (31% of the total cancers diagnosed).

Benefits assessment

The impact of early detection programmes in different European countries was reviewed in 2012.

It is a systematic review of the literature that assesses mortality behavior among women invited to the program, actively screening women and unsifted women. It includes 17 mortality trend studies, 20 mortality based impact studies, and 8 case-control studies.

Of the 17 trend studies, 12 quantify the incidence of breast cancer mortality and, in which they compare the deadlines before and after screening, estimate a decrease from 28% to 36%.

The results of impact studies based on mortality, cases and controls are methodologically more acceptable.

In mortality based impact studies, the mortality rate decreased by 25% [odds ratio or Odss Ratio 0.75 index; and the confidence interval, 95% (0.69-0.81)] among invited women, and 38% [ Odss Ratio 0.62; and a 95% confidence interval (0.56-0.69)] among women included in active screening.

In case-control studies, mortality decreased by 31% [ Odss Ratio 0.69; and the confidence interval, 95% (0.57-0.83)] among invited women and 48% among pregnant women.

This review takes into account the methodological validity of study designs and statistical analyses, the main reason for the debate on mortality trends.

In summary, the decrease in mortality among women invited to the programme ranges from 25% to 31% and the decline among women actively screened between 38% and 48%.

This study also evaluates overdiagnoses: the mean excess cancer is 6.5% compared to those diagnosed without screening (1-10% variability among studies).

This estimate is far from the values obtained in mortality trend studies (higher or equal to 30%).

Probably this difference is explained by the existence of less adequate studies and analyses.

Evaluation of false positives poses a cumulative risk for a woman screening every two years between 50-69: 17% in non-invasive procedures and 3% in invasive procedures (biopsies).

For every 1,000 pregnant women in 20 years:

· Breast cancers diagnosed: 71 cases.

· Decrease in mortality: Avoid 7-9 deaths (30 estimated cases).

· Overdiagnostics: 4 cases (of the 67 expected cases).

· False positives: 200 cases (170 only with noninvasive procedures and 30 with biopsy).

Other recent European studies (published between 2010 and 2012):

Italian region of Florence: Among women aged 50 to 59 years, it is estimated that mortality has decreased by 43% and among those aged 60 to 69 years by 48%, while the rate of overdiagnosis is 10%. The overall cost of saving a life is lower than that of a diagnosed tumor (cohort study and follow-up of an average of 15 years to 51,096 women between 1971 and 2008).

In Nijmegen, Holland, 55,925 women (50-69 years) were monitored (cases and controls) between 1975 and 2008, with the estimated benefit of the 35% decrease [ Odss Ratio 0.65 index and 95% confidence interval (0.49-0.87)]

Comparative studies conducted in Sweden and England among women aged 50 to 69 show that the absolute benefit of saved lives is 8.4 and 5.7 per 1,000 women invited to raise 20 years. The number of overdiagnoses per 1,000 women was 4.3 and 2.3 respectively.

In absolute terms, 2-2.5 lives were saved for each overdiagnosis performed.

In 2009, the United States Preventive Services Task Force conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of screening programs in the U.S. and concluded that among pregnant women aged 50-70 years, mortality decreased by 16.5% compared to women who were not on screening programs.

Regarding the target age of programs, there is a consensus between 50-69 years, since the effectiveness of screening has been demonstrated in different trials, among which have been mentioned above.

However, the extension of screening to younger women (40-49 years) generates debate, probably because clinical trials that laid the foundations for population screening did not show a significant decrease in mortality among younger women, although recent studies suggest that at this age it is also effective, although to a lesser extent.

Regardless of their incidence on mortality, the discussion on the age group also addresses the cost-risk-benefit relationship, since cancer is lower, tumors grow faster and chest density decreases (sensitivity and specificity of mammography).

The lack of agreement generates contradictory messages between the population and professionals, provoking numerous opportunist siblings before the age of access to programs.

In the case of women over 70, although both the incidence of breast cancer and the sensitivity of mammography are greater, they have been discarded from population programs, as a low participation rate was expected.

Conclusions

It can now be said that a woman included in the kidnapping program has a lower risk of death from breast cancer than another woman who is not on the screening program, and the benefit is estimated to be between 16.5% and 48%.

These saved lives themselves justify a screening test, although a rate of overdiagnosis and false positives must be approved.

References

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia