The Dalton Daltonism

2017/06/01 Etxebeste Aduriz, Egoitz - Elhuyar Zientzia Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

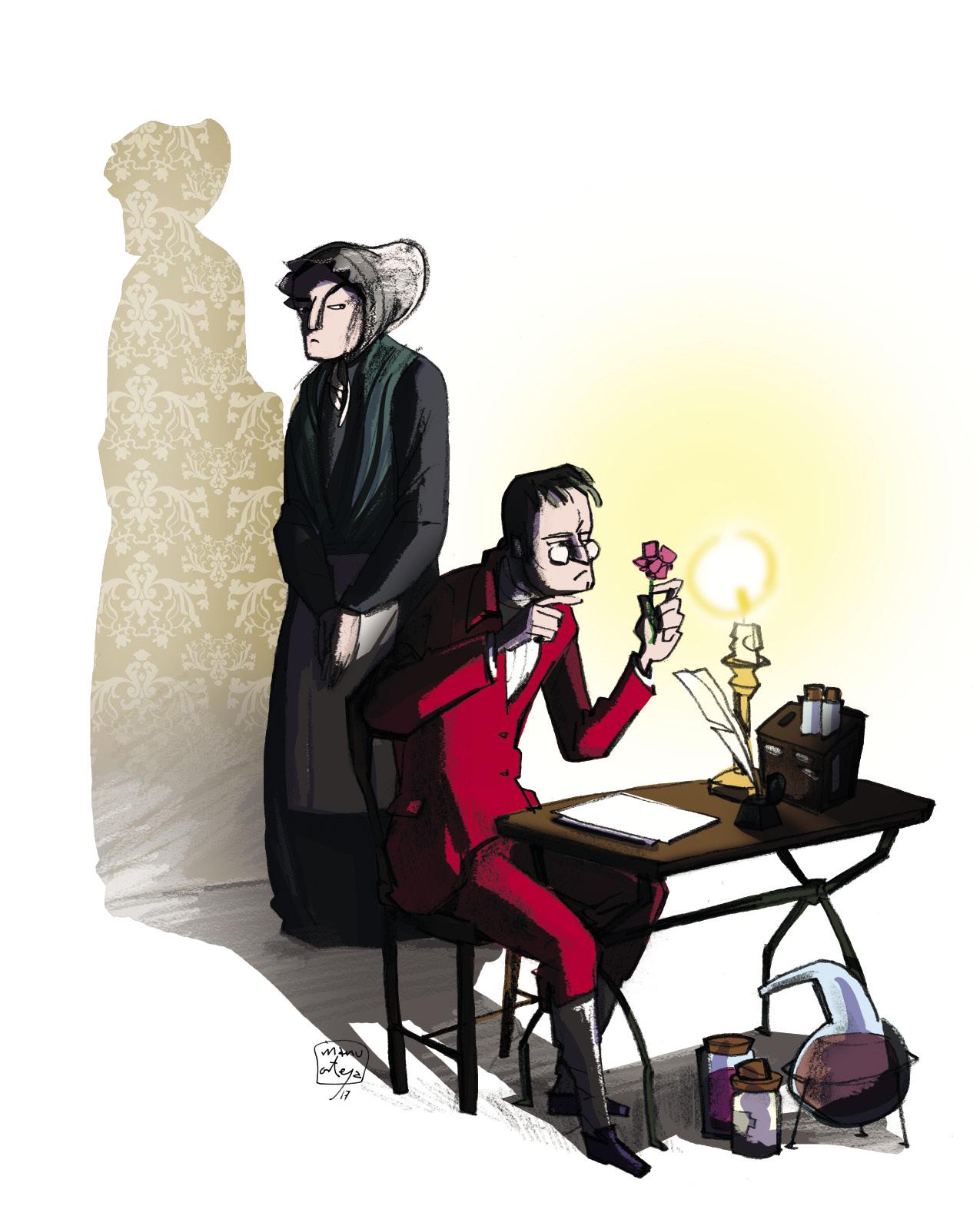

He looked at the geranium, surprised, trying to understand what he was seeing. It was night and, in the light of the candle, the flowers were blue during the day I was seeing red. When that surprising phenomenon began to appear to those around him, however, he was even more surprised: no one saw the change of color, except the brothers.

“This observation showed that my vision was not the same as that of other people,” wrote John Dalton in Extraordinary facts relating to the vision of colours, published in 1794. In fact, despite his atomic theory, his work with gases, etc. It became famous, John Dalton's first scientific work focused on the disturbance we now know as daltonism.

In that work he investigated himself. “I always thought, although I didn’t say it many times, that some colors were not well assigned,” he says at the beginning of the work. “In my dedication to science optics caught my attention and I learned very well the theories of light and colors, without realizing that my vision had peculiarities. But I paid no special attention to the practical discrimination of colors, since I thought the problem was in its confusing nomenclature.”

He began studying botany in 1790 and realized that he had problems distinguishing various colors: “I often asked people, seriously, that a flower was pink or blue, but they thought I was taking my hair,” he wrote. “But I was not sure of the uniqueness of my vision until in the autumn of 1792, by chance, I saw the flowers of the zonal Geranium in the light of the candle. The flowers were roses, in fact, but I saw them as blue as the sky in daylight, and in the light of the candle it changed surprisingly, but nothing of the blue, its color was the one I called red, a color that contrasts very much with the blue.”

Seeing that this only happened to his brother and him, he thought it was going to be a hereditary alteration and began to investigate the subject. To begin with, he asked a friend who dyed a silk ribbon of various colors and could compare his perception of colors with that of others.

“For me the blood is no different from what is called green bottle. And it’s hard to distinguish if socks are stained with blood or mud,” he described. “I have the example of my green from the ear. For me it is not very different from red. The bay leaf coincides with the red lacre. In this way it can be concluded immediately that I see green or red different to the rest, or both”.

He described in detail how he saw the color spectrum. “I only see two or at most three colors, which I would call yellow and blue, or yellow, blue and purple. In my yellow come the red, orange, yellow and green of others, and my blue and purple coincide with the others. What others call red is for me as a shadow or a lack of light. Orange, yellow and green I see it as colors that go from life to low, or as different shades of yellow, I would say.”

In addition to his brother, he found more people who saw different colors. “Once I explained the subject to my 25 students, two realized that it was like me. And again the same thing happened with another [...] I have not found any case that occurs at once in parents and children […] It is important to note that I have not found cases of women with this specificity”.

In the end, Dalton concluded that the vitreous humour of his eyes was dyed in blue. And to confirm this, he asked his disciple and friend Dr. Joseph Ransome to remove his eyes and study them when he died. Ransom did so in 1844. He opened one of Dalton's eyes and poured his content into a magnifying glass. The vitreous humor was normal, transparent and without color. With the second eye he did another test: behind he made a hole and from there he looked to see if he looked green and red like Dalton. But he saw green green and red red.

Today we know that daltonism is a consequence of a series of genetic errors that affect photosensitive cells called retinal cones. 200 years after Dalton described the rebellion, in 1995, researchers at the University of London reexamined their eyes. In this case, a DNA study was conducted. And they saw that it had deuteriopia, that is, the cones of Dalton lacked photopigments sensitive to green color (average wavelengths).

Bibliography: Bibliography:

EMERY, A. R. R. (1988): “John Dalton (1766-1844)”. Journal of Medical Genetics 25(6) 422-426.

HUNT, D. M.; DULAI, K. S.; BOWMAKER, J. C.; MOLLON, J.D. (1995): “The chemistry of John Dalton’s color blindness”. Science 267, 5200, 984-988.

THE COLLEGE OF OPTOMETRISTS. “John Dalton – A Visual Error”

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia