Discovery of the mystery of the probe Galileo

2001/03/27 Elhuyar Zientzia

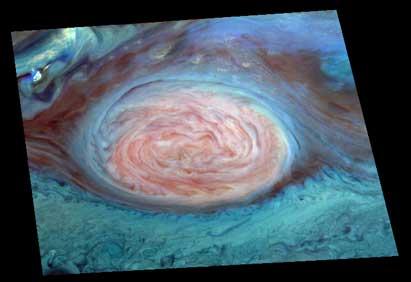

NASA launched the Galileo probe on 18 October 1989 to investigate Jupiter and its satellites closely. He made a long journey and approached the Jupiter system in December 1995. He entered the orbit around the planet and began to collect photographs and data, among others, from the great stain of Jupiter that we can see in the image.

To refer to the location of the probe, the Delta Velorum star was selected. It is a brighter star than the North Star, one of the 50 brightest stars in the sky. However, the probe lost the image of the star. NASA technicians began to look for some failure of the probe. The star scanner worked correctly and no damaged device was found. Finally, NASA engineer Paul Fieseler of JPL concluded that the problem should be in the star.

An instrument carrying the probe is scheduled for star tracking, but tracking is based on star brightness. When the star disappeared, Fieseler reviewed the list of variable brightness stars and Delta Velorum was not there. With the help of amateur astronomers from the southern hemisphere, Fieseler discovered that star should be on the list. The results were published by the International Astronomical Union.

"Variable brightness stars are typical, but it's been a surprise that such a bright star is so changing and no one knows about it," says Fieseler. The engineer requested data about the star through an email on the Internet and amateur astronomer Sebastian Otero of Buenos Aires replied that he had seen this loss of brightness four times.

Although the Galileo probe was not designed to investigate the stars, astronomers Otero and Christopher Lloyd from the UK used data from probe problems to predict the next two glitter losses. Astronomers from South America, Africa and Australia confirmed that the prediction was good.

Delta Velotum is a set of at least five stars, so brightness losses depend on their relative position. Research has found that the highest brightness is not produced by a star but by two stars orbiting each other. Eclipses between the two and, therefore, brightness losses can be predicted from the peridiode of the orbit.

The Galileo probe was programmed to catch normal brightness. If I had not lost my mark, we would have no new discoveries. The brightness change is small but occurs every 45 days and lasts a few hours. It is surprising that so far no one has realized it.

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia