From Removal to Addition: Accumulating Metals

2025/03/01 Aldalur Urresti, Eider - Tecnaliako ikertzailea, Ingeniaritza Mekanikoan doktorea Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

Throughout history, manufacturing technologies and the industry in general have evolved to the foundry, forming and machining technologies that today are the main pillars of the metal industry worldwide. The technological advances of recent years make it necessary to add to this list an innovative manufacturing technology: additive manufacturing.

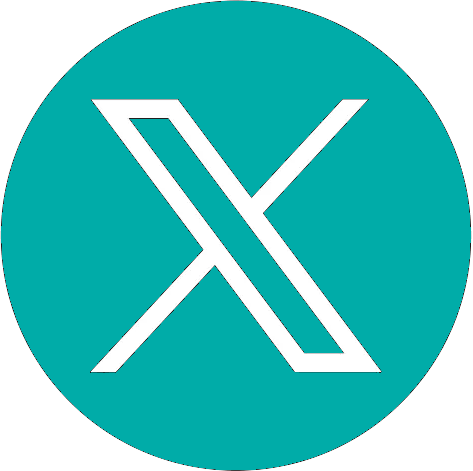

The remains of the first man-made stone tools take us back 3.4 million years, to the Stone Age. It was at this time that man first began to work on stones, striking them against each other, to manufacture tools, weapons and sharp edge tips by extraction. Thus, the first antecedent of current machining technologies was established. Then, during the Neolithic period, the use of stone as a basic element in the manufacture of artifacts was stopped and the cultivation of metals began, initially through cold hammering (the precursor of the current conformation), followed by the casting of minerals (the precursor of modern casting).

Since the laying of the first modern machining stone by man during the Paleolithic period, these manufacturing technologies have undergone considerable development, as shown in Figure 1. This path is witnessed, for example, by the great Italian sculptor and painter of the renaissance Michelangelo Buonarroti, David from 1501 to 1504, a spectacular 5.17-metre sculpture. To sculpt this work, Michelangelo Carrara started from a dense block of marble from the quarries. Although years have passed, the same formula is still used in today’s most widely used manufacturing technology, machining. Some things remain intact.

However, manufacturing technologies have undergone the greatest development since the end of the 18th century, thanks to the advances brought by industrial revolutions. In 21st century manufacturing, machines and automation have taken the place of Michelangelo’s hands. It is said that today we are in the age of Industry 4.0. Intelligent production systems and information technologies are integrated into industrial systems, and this cyber-physical integration creates high-efficiency intelligent factories capable of manufacturing high-quality products.

A change of paradigm

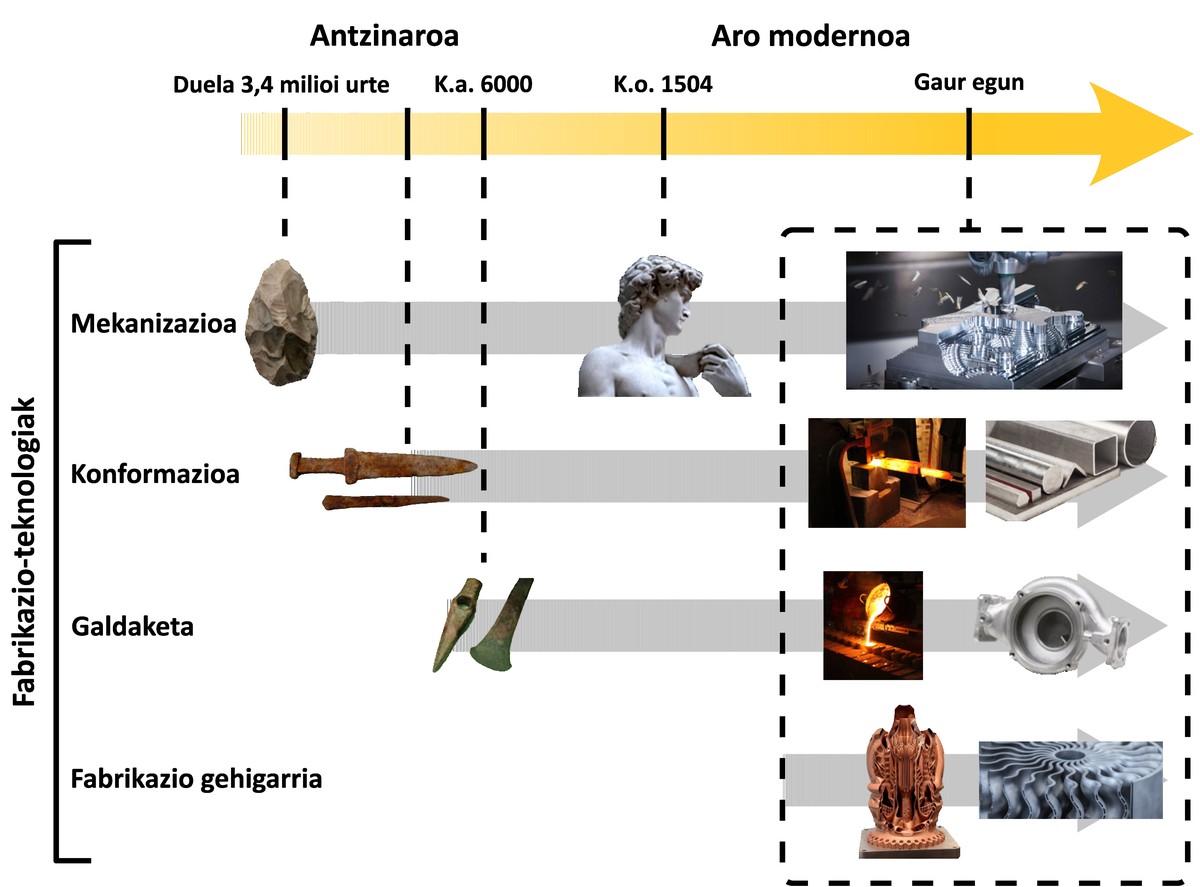

Like Michelangelo and those first humans of the Paleolithic, the process of manufacturing parts by machining starts from a block, from which the material is removed, obtaining the final shape of the part. In additive manufacturing, on the other hand, the manufacturing paradigm changes: from a three-dimensional (3D) digital design, material is added layer by layer, thus manufacturing a physical object (Figure 2).

Additive manufacturing was first used in 1986 when stereolithography was created; this technology uses ultraviolet rays to create photosensitive polymers layer by layer. Originally, additive manufacturing was also called 3D printing, and was originally developed to make rapid prototypes. In recent years, however, the accuracy, repeatability and reliability of additive manufacturing techniques have increased, and some additive manufacturing technologies are now considered viable for industrial production. Today, additive manufacturing can produce high consistency parts in a wide range of materials such as polymers, metals, ceramics, composites, etc.

Such technologies are expected to be disruptive; they will transform the global production network and become an indispensable tool for various industrial sectors. In fact, additive manufacturing responds to the development of the production system proposed by Industry 4.0, which paves the way from the initial design to the final piece.

Why add it?

One of the main advantages of additive manufacturing is the ability to manufacture parts of high geometric complexity. The use of other technologies would make it impossible to produce parts of this type, such as hollow parts, with complex details or with internal meshes. Through additive manufacturing, a high degree of freedom in design is achieved, which is essential for applications that require a low weight, or for parts that would have many components if manufactured with traditional techniques to be single-component. Here is a well-known example: General Electric installed fuel injectors produced by additive manufacturing in its CFM LEAP aircraft engine; the new injectors were made in a single block and were 25% lighter than the initial eighteen-component system.

In addition, additive manufacturing allows the final product to be customized. This possibility is limited in traditional manufacturing techniques due to the cost involved. In fact, it is often necessary to modify the moulds used to produce the parts and the design of the tooling, the cost of which is usually not feasible.On the other hand, through additive manufacturing, since the parts are designed and manufactured directly, it is feasible to make unique and customized parts.

On the other hand, through additive manufacturing technologies, pieces close to the final geometry are obtained, because the material is only implanted where it is really necessary. Thus, the rate of exploitation of raw materials is very high (see Figure 2). For this reason, additive manufacturing can be a competitive option for the materials used (titanium, nickel alloys, etc.) when they are expensive, such as in the aeronautical industry.

Finally, additive manufacturing technologies have proven to be highly suitable for reducing energy consumption, reducing material waste and eliminating or reducing machining steps. For example, studies have shown that the widespread use of additive manufacturing would reduce energy demand by 27%.

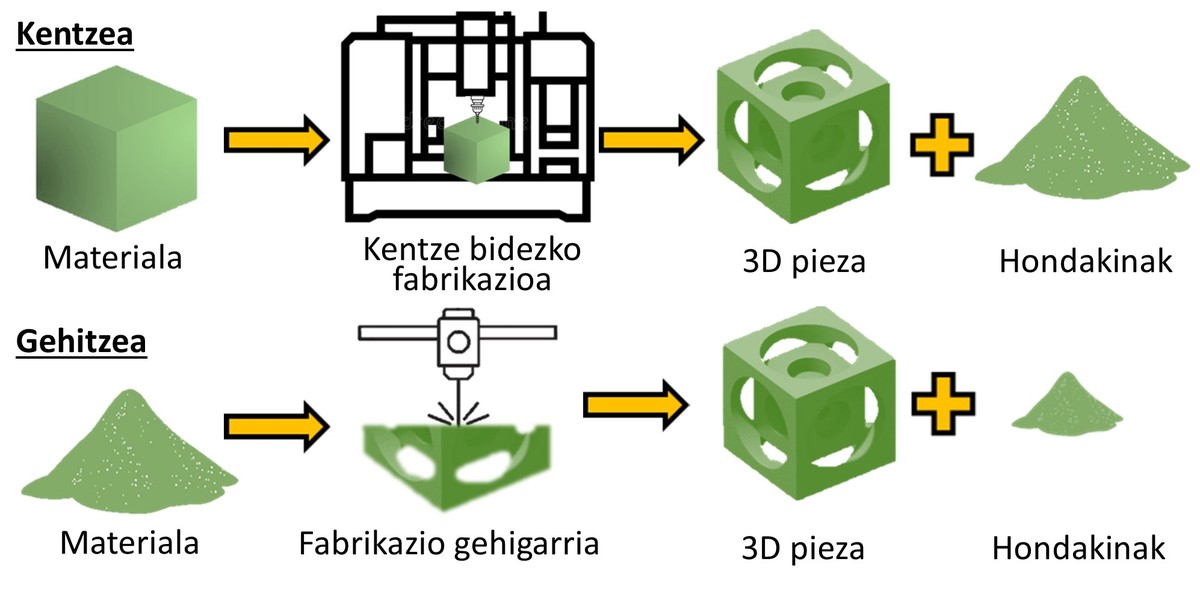

Accumulating the metals

Within additive manufacturing, each type of technology is a particular combination of an energy source, the format of the material to be used and a mobile system, each combination serving a particular application. According to standard terminology created by the ASTM Association (American Society for Testing and Materials), additive manufacturing technologies are classified into seven categories, four of which can be used in metallic materials, as shown in Figure 3. One of these categories is the so-called directed energy deposition (DED). In all the techniques that are collected there, the material, as it is fed, is melted by the energy source. In DED technology, the material can be fed in two formats: as yarn or as powder. The use of yarn instead of powder has certain advantages: it reduces the price, increases the efficiency of the use of the material and minimises occupational safety and health risks. Alternatively, a laser, an electron beam or an electric arc may be used as the energy source for melting the material. Specifically, in the wire arc additive manufacturing (WAAM) process that I have studied in my thesis, the material is fed as a wire and melted by an electric arc.

At present, WAAM technology has become an interesting manufacturing process because it allows the manufacture of metal parts of large size and medium geometric complexity at low cost. In terms of features, the WAAM technology is similar to an automatic welding process in that the power source melts the wire through an electric arc and, through the handling system, deposits the molten metal on the base material layer by layer until the target geometry is completed.

Thread and bow

Depending on the welding source used, there are different types of WAAM processes. In fact, I have worked on the WAAM process based on gas metal arc welding (GMAW) technology, which may be of interest for industrial use due to the high productivity rates (1-10 kg/h) it achieves.

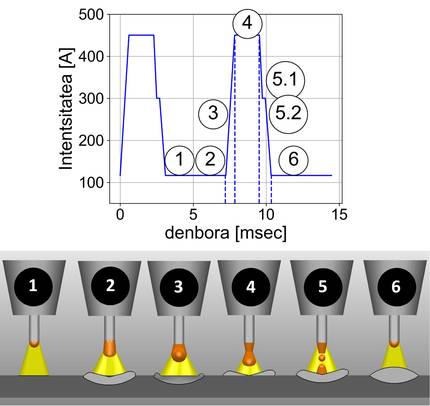

In the GMAW technology (see the right-hand side of Figure 3), the consumable electrode is the wire. That is, the material is positioned such that an intensity signal is applied to the wire and an electric arc is formed between the wire and the workpiece. This electric arc allows the metal to melt and the metal droplets are transferred from the wire to the workpiece. FIG. 4 illustrates the correlation between the molten metal droplet generation process and the intensity signal.

This transfer can take place in a variety of ways: as a spray, in a globular fashion, or by short circuits. In recent decades, welding sources with high frequency control strategies have been used to control the transfer of material. The shape of the intensity signal (waveform, frequency, etc.) applied to the yarn by these control strategies. They are defined. I have studied the transfer modes available for steel and aluminium alloys in my thesis; as I have seen, the transfer modes have a significant impact on the heat input to the part, which determines both the geometry of the implant and the productivity. I have also studied the effect of transfer modes on the degree of porosity achieved in aluminium.

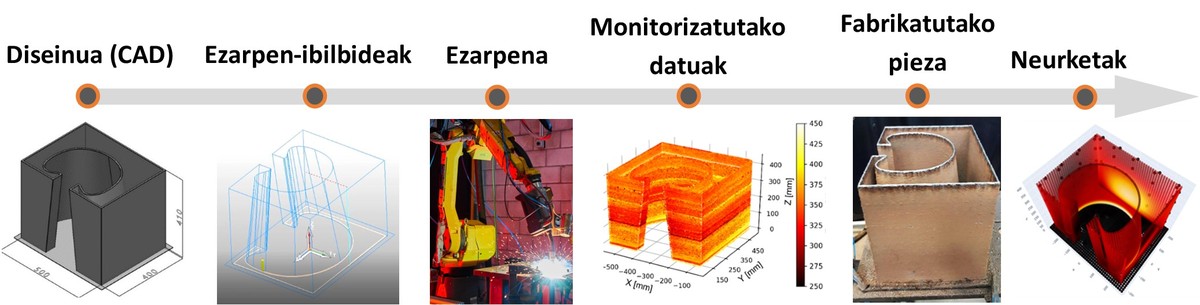

To conclude, Figure 5 shows the path to follow for the manufacture of parts from the initial design by means of the WAAM process based on GMAW technology. Once the design is defined, the part is divided into layers and the implantation paths of each layer are created. The process parameters are then determined and the part is manufactured by means of a robot or a CNC machine. During manufacturing, the internal parameters of the process are monitored, as well as those of the sensors installed in the machine. The process is controlled by data monitored in real time and finally the piece obtained is measured to ensure that it is within the tolerance.

The main objective of my thesis has been to establish the bases so that the machines can travel as autonomously as possible from the initial design to the final piece. Give it to a button and, like Michelangelo’s hands, let the robot start manufacturing parts on its own.

The bibliography

Assisted by Aldalur, E., Assisted by Suárez, A., & Veiga, F. 2021. “Influence of Wire Arc Additive Manufacturing metal transfer modes on droplet formation, heat input, microstructure and porosity of as-built Al-Mg alloys”. Journal of Material Processing Technology, 2021, 297, 117271.

More places to stay in Cunningham, C. I'm talking about R., In Flynn, J. More about M., I am interested in Shokrani, A., More places to stay in Dhokia, V., & Newman, S. I'm talking about T. 2018. “Invited review article: Strategies and processes for high quality wire arc additive manufacturing”. Additive Manufacturing, 22, 672–686.

Images from Dilberoğlu, U. More about M., According to Gharehpapagh, B., More places to stay in Yaman, U., In Dole, M. 2017. “The Role of Additive Manufacturing in the Era of Industry 4.0” Procurement Manufacturing, 11, 545–554.

The General Electric. 2017. “GE Global Research, 3D Printing New Parts for Aircraft Engines”. More places to stay

in Herzog, D., More places to stay in Seyda, V., It's Wycisk, E., & Emmelmann, C. 2016. “Additive manufacturing of metals”. Acta Materialia, 117, 371–392.

ISO/ASTM. ISO/ASTM 52900. 2015. Additive manufacturing - General principles - Terminology. International Standard, 5, 1–26.

Assisted by Suárez, A., Assisted by Aldalur, E., More places to stay in Veiga, F., The Artaza, T., In Tabernero, I., & Lamikiz, A. 2021. “Wire arc additive manufacturing of an aeronautic fitting with different metal alloys: From the design to the part”. Journal of Manufacturing Processes, 64, 188-197.

According to Sun, C., To Wang, Y., More places to stay in McMurtrey, M. According to D., By Jerred, N. According to D., According to Liou, F., & Li, J. 2021. “Additive manufacturing for energy: A review”. Applied Energy, 282.

Assisted by Williams, S. More about W., Assisted by Martina, F., Assisted by Addison, A. According to C., It's about Ding, J., Assisted by Pardal, G., & Colegrove, P. 2016. “Wire + Arc additive manufacturing”. Materials Science and Technology, 32(7), 641–647.