Lineage and taxonomy: a milestone in the history of science

2025/03/01 Zabaltza Pérez-Nievas, Xabier - Gaur Egungo Historiako irakasleaUPV/EHU Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

Charles Lineus spent the rest of his life trying to organize all the creatures of nature. This great Swedish naturalist did not name only animal and plant species. He also classified minerals and many other things, including the so-called human races. Prejudice, always in Latin, was the creator of the taxonomy and primatology used in all branches of biology today.

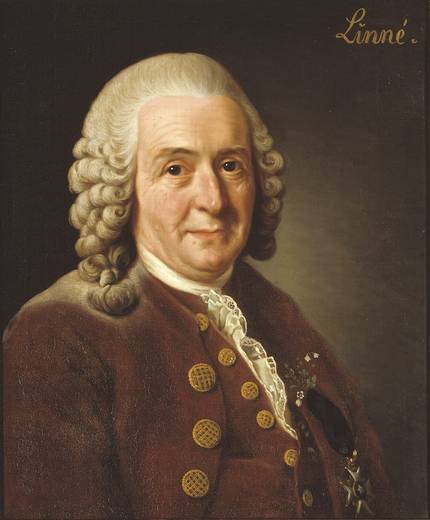

Before we begin to talk about the father of taxonomy, Carlos Lineo (1707-1778), it is advisable to specify his name, which is often mispronounced. Carl Linnæus was baptized in Swedish, but after 1761 he became the father's son and was named Carl von Linné. In Latin, he wrote most of his works in a language understood by all European scholars, signed Carolus Linnæus until 1761, and Carolus a Linné since then. The Basque Government decided in 2017 that its name is ‘Lineo’ in Basque.

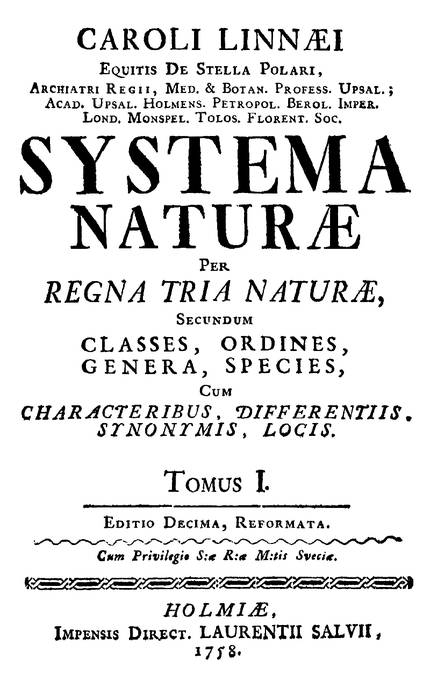

It is difficult to magnify the influence of Lineo in the history of science. In 1735 he published a 12-page pamphlet: Systema Naturae, an attempt to classify the three kingdoms of the Emperor of Nature, namely animals, plants and minerals. This triangular division was not his idea, as it was popularized by the alchemists of the 17th century. Lineus introduced man among the animals, but for a long time a fourth kingdom was in force: Regnum Hominale, exactly. The twelfth edition of Systema (1766-1768), the last of which appeared before his death, contains 2,400 pages in three volumes. The tenth, dating from 1758, is considered the starting point of modern zoology, since it was here that he established the twin names of animals, composed of genus and species. In 1753, Species Plantarum was published. Between the kingdom and the genre he pared the class and the order. Heir to a tradition that makes liver up to Plato, these categories were not invented by Lineo either, but he used them systematically. Although he never uttered some of the words that have been attributed to him (“God created, Lineok sheba”), he saw himself as a new Adam, insisting on naming all beings, living and inanimate. Always in Latin, it gave a scientific name to 7,700 plant species and 4,400 animal species.

Lineus said that species have been created by God and are fixed: they cannot appear, change or become extinct. He did not know the theory of evolution, which was published by Darwin and Wallace in 1858. However, in his later years he began to suspect that some species could be created by hybridization. As for ours, in 1758, in the tenth edition of the book Systema Naturae, he baptized us with the name Homo sapiens, although the term Homo diurnus also appears in it. We are divided into six varieties. Of them, four on the continent are continental and coloured. Homo sapiens americanus is red and is organized according to custom. Homo sapiens europæus is white and is organized according to the laws. Homo sapiens asiaticus is yellow and is organized by opinion. Finally, Homo sapiens is an afer black and is organized according to the whim. But there are two other varieties. Within the so-called Homo sapiens ferus he introduced the so-called wild children, for example, both of which are said to have been found in the Pyrenees in 1719. Homo sapiens monstrosus is composed of those who are abnormal to Lineus: (Lapland) the dwarfs of the Alps, the giants of Patagonia, the Hottentots of a single testicle (i.e. the Khoekhoes), the Chinese of a large and conical head, the Amerindians of the oblique and oppressed head of Canada, and, in Europe, the girls whose abdomen is lightened by the belching.

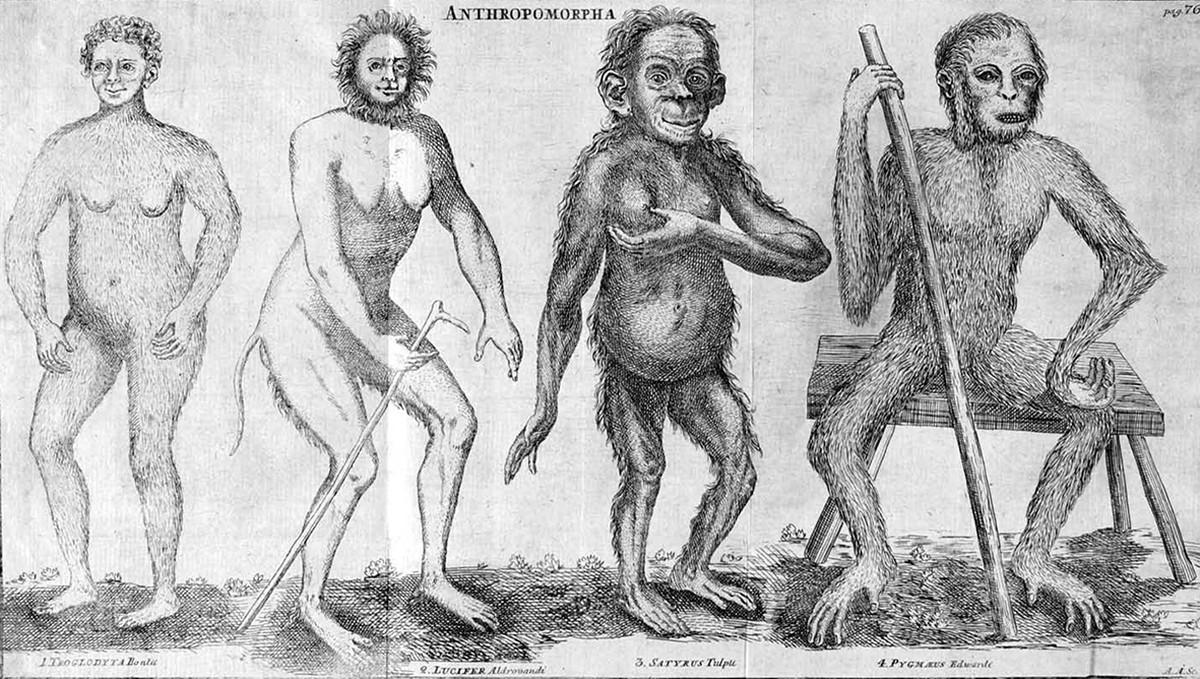

Even more so. Homo sapiens or Homo diurnus was not the only human species he described in 1758. The imaginary account of Dutch physician Jacob de Bondt and Swedish traveller Nils Matson Kiöping also established the species Homo troglodytes or Homo nocturnus. Contrary to what is commonly thought, it was neither a chimpanzee nor a bonobo nor, although this is not so clear, any of the three orangutans. It is probably a distorted picture of the Indonesian women of today's fleas and albino men. As if that were not enough, in addition to the authors mentioned, according to the Italian naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi and the French philosopher Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, he reported on Homo caudatus hirsutus, or ‘man with tail and hair’. In that case, he was referring to the baboon on both sides of the Red Sea, which was sacred in ancient Egypt, elevated and humanized. In 1760 he classified these two imaginary human varieties into the genus Simia. In 1771 he introduced three species of gibbon in the taxon Homo lar. Educated in Lutheranism, Lineus was convinced that God is rational and that, as a result, there can be no genus of one species. In addition, in his time, the Scala Naturae, or ‘great chain of being’, had a great sapa. According to this paradigm that has been developed since ancient times, God is at the top of the beings and the four elements (earth, water, air and fire, in that order), at the base, always in the descending and uninterrupted section, since “Nature does not jump”. At least one species of human being was needed between humans and other animals. There are also polyps between animals and plants, and corals between plants and minerals (and between God and man, nine orders of angels).

It has been observed that the classification of human beings is full of racism and other prejudices. In fact, although it has been considered an ‘Enlightenment’ from a totally Eurocentric perspective, Lindo’s period was very dark. The abduction, trafficking and enslavement of Africans were legal and the colonization of the entire world was taking place. For this reason, his attitude is worthy of consideration, because, as has been said, he united all flesh and blood men into one species. The multiple authors who lived after Linino divided them into several species. They went even further with Ernst Haeckel in 1889 and Giuseppe Sergi in 1911, who were classified not only in some species but also in some genera. Haeckel’s case is particularly striking because he was a top scientist. Harex named the third kingdom of life after Beast and Plantae in 1866: Protist, single cell organisms (with nuclei).

In 1735, Lineus, in the first edition of Systema Naturae, established the Quadrupedia (‘four-legged’) class within the Animal kingdom, taking its name from Aristotle, and within it the Anthro-pomorpha (‘human-like’) order, taking its name from John Ray. The order included three genres, Homo and Simia among them. In 1758, in the tenth celebrated edition of the same book, he renamed the class Mammalia (‘mammals’) and the order Primates (‘first’ in the hierarchy of Nature beings). Both of them, much changed, remain in force. In fact, multiple species have been detected in this three century. In addition, in recent decades there has been a revolution in the classification of organisms by molecular research. As a result, the taxonomy has had to adapt to the rules of the cladistics and the species have multiplied. Unlike Lino’s time, species are now classified not by obvious characteristics, but by genetic relationships between them. In particular, in addition to Homo sapiens, the Swede correctly described 32 primate species among the 505 recognized until 2016. However, the bats and colugos, which he placed in this order, are not primates (just as the lazy ones are not anthropomorphs). It has been explained that other species have existed only in their superstitious mind and in those like hers. Also, like most researchers of his time, he did not distinguish between orangutans and chimpanzee (and bonobo). As a curiosity, I will add that the French zoologist Henri-Marie Ducrotay de Blainville, who was the imitator of Lino, created the categories Secundates, Tertiates and Quaternates for the grouping of mammalian orders in 1839. Needless to say, he had no success.

Lineo didn’t apply the Latin double names only to animals and plants. It was also tested with fungi and some microscopic organisms. For all of them, in doubt, he suggested Regnum Neutrum or Regnum Chaoticum in 1767. Most of them were incorporated into the Fungi kingdom by Robert Whittaker in 1959. Although it did not have an echo, Lino also used the twin names with Lapides or ‘stones’ because, in his opinion, they make up the third kingdom of Nature. As a sign of his obsession with classifications, he also formed taxons for a variety of other accounts, such as medicines, diseases, and foods. Those without a twin name, but always in Latin.

As a result of the revolution in biology, the entire system of Lineus was overthrown. In 1990, microbiologists Carl Woese, Otto Kandler and Mark Wheelis built three regions or ‘domains’ over conventional kingdoms. Plants, animals, protists and fungi, which contain the cell nucleus, were placed in the Eukaryota domain, recovering the concept launched by Édouard Chatton in 1925. The protists were then divided into several supergroups. The other two domains, which do not contain a cell nucleus, are: Bacteria, which was organized as a kingdom by Herbert Copeland in 1938, and Archæa, which contains organisms described by Woes himself and George Edward Fox in 1977. Although microscopic, archaea is closer to eukaryotes than to bacteria. Latin names continue to be used in all three regions. Lee Barker Walton proposed the term Bionta in 1930 to unite all living things into a single taxon.

Despite the criticisms, Linino’s taxonomy could be an antidote to the anthropocentrism of our civilization. After all, in its organization, Homo sapiens is only one of the millions of species of the Imperium Naturae. In fact, the words homo (‘man’) and humilis (‘humble’) have the same origin, since both come from the pre-European root *dhghem- (‘earth’). As for the word ‘man’, it could be associated with the words *zoni in preface and ‘zohi’ in today’s Basque language. Thus, ‘man’ in Basque and human/humain/uman in our hare simply mean ‘the inhabitant of the Earth’, because the whole planet is the Human People, which we share with the other two.

Of Gratitude

The late Gunnar Brober (Lunds universitet, Sweden), Raymond Corbey (Universiteit Leiden, The Netherlands), Aulus Gratius Avitus (Schola Latina Universalis, UK) and the late Colin Groves (National University, Australia).

The bibliography

[1] By Barsanti G. 2005. A lunga pazienza cieca. Storia dell’evolucionism. Assisted by Einaudi, Turin.

[2] Blunt W. and Stearn W.T. 1971. Pictures of The Compleat Naturalist: From A Life of Linnaeus.Viking Press, New York.

[3] Corbey R. and Theunissen B. (by the Ed. ). 1995. Ape, Man, Apeman: Changing Views since 1600. Leiden University, Leiden.

[4] By Frängsmyr T. (by the Ed. ). 1983. Pictures of Linnaeus: The man and his work. University of California Press, Berkeley.

[5] By Groves C. 2008. Pictures of Extended Family: The Long Lost Cousins. A Personal Look at the History of Primatology. Conservation International, Arlington.

[6] By Koerner L. 1999. Pictures of Linnaeus: From Nature and Nation. Harvard University Press, Cambridge/London.

[7] Janson H.W. 1952. Apes and Ape Lore in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Warburg Institute, London.

[8] Linnæus C. Several works have been used, most of which are Systema Naturae. The first edition dates back to 1735. The tenth contains two volumes: the first (1758) on animals and the second (1759) on plants, the third, on minerals, which was not published. The twelfth, in three volumes, dates from 1766-1768. After the death of Lineus, Gmelin published the thirteenth edition (1788-1793).

[9] Lovejoy A.O. 1936. Pictures of The Great Chain of Being: A Study of the History of an Idea. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

[10] By Pulteney R. 1781. A General View of the Writings of Linnæus. I'm talking about T. By Payne and B. White, from London.

[11] By Roberts J. 2024. Pictures of Every Living Thing: The Great and Deadly Race to Know All Life. Random House, New York.

[12] Rowe N. and Myers M. (by the Ed. ). 2016. All the World’s Primates. Pogonias Press, Charlestown.

[13] Zacharias K.L. 1980. The Construction of a Primate Order: Taxonomy and Comparative Anatomy in Establishing the Human Place in Nature (1735-1916). According to the Ph.D. Dissertation, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore.