Without finding the last common ancestor of Neanderthal and modern man

2013/10/30 Carton Virto, Eider - Elhuyar Zientzia Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

.jpg)

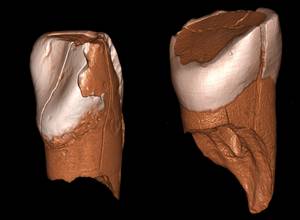

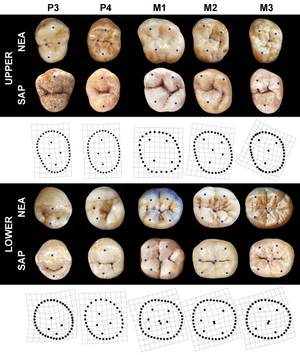

To know what was the last common ancestor of the Neanderthal and the modern man, a group of international researchers has addressed the teeth of the fossil record, and the title of the article published in the journal PNAS clearly indicates the result: “No known hominin species matches the expected dental morphology of the last common ancestor of Neanderthals and modern humans”, that is, none of the known hominid species coincides with the dental morphology of the Neanderthal and the last common ancestor of modern man. In addition, the results indicate that this common ancestor can be older than expected: one million years ago, and not, as suggested by techniques based on genetic analysis, 450,000 years ago.

The research team has studied 1,200 teeth of 13 hominid species to reach this conclusion and has used and proposed quantitative analysis techniques to check the phylogeny of human species. Among the studied are the species of the genus Australophitecus, Paranthropus and Homo, which lived in Africa and Europe, among them the species Homo antecessor found in Atapuerca, called to be found a common ancestor. In fact, many of the samples have been collected at the site of Atapuerca.

The research has been divided into two main parts. On the one hand, they have calculated how the teeth of the last common ancestor of Neanderthal and modern man would be, based on the characteristics of known human species and on the phylogenetic relations between them. On the other hand, these theoretical teeth have been compared with the fossil teeth known to see if any species was the ideal candidate to be the last common ancestor of the Neanderthal and modern man. It has not been so.

One of the members of the group is the paleoanthropologist Aida Gómez Robles, from the University of George Washington, who says that “the main strength of this methodology is that it is an objective instrument to evaluate hypotheses on phylogenetic positions of fossil species.” In fact, “on too many occasions” these hypotheses are based on descriptive studies that are not quantifiable or nullifiable and not on quantitative analysis. “Our work, however, allows not only to calculate the most probable form of the ancestors, but to determine which species are incompatible with this position of ancestor,” said Gómez Robles.

Building models by building models

The methodology used in research is not new. Geometric morphometry is a very common practice in the field of evolutionary biology, and is increasingly used to investigate human evolution, as it provides information that cannot be obtained using more classical morphological descriptions. In this case, this quantitative methodology has been used to analyze the shape of the previous pins. On the other hand, the methodologies for the reconstruction of the forms of the ancestors were also used since the 1990s. “Methodologically, the main contribution of our work has been the joint use of these two components and the comparison of the forms of the calculated ancestors with the real species collected in the fossil record, which allows us to calculate the probability of being ancestors”, explains Gómez de Robles.Gomez-Robles, and together with her, we use the Centro Nacional de Investigación de la Evolución Humana (CCPSU) In this way, 12 phylogenetic scenarios have been analyzed that are distinguished in the dating of common species and ancestors. According to Gomez-Robles, this allows comparing the different hypotheses of human evolution: not only what is possible and what is not, but what hypothesis is more likely.

However, Gomez-Robles warns that “if it was demonstrated that the real phylogeny of hominids is radically different from the scenarios considered in the article, the compatibilities and incompatibilities observed could be modified”. And the same if it is possible to add more samples of selected species, or if it is possible to add new species. In fact, “as in all paleontological research, the scarcity and heterogeneity of the fossil record is also a limit,” says Gómez Robles.

In this sense, Gomez-Robles shares the vision of the paleontologist of the Natural History of Paris, Asier Gomez-Olivency: “As its authors say, the amount of fossils in Africa is very small in the middle Pleistocene. Some skulls are known, but few teeth. The African fossil teeth of 500-900 thousand years ago are necessary to compare their morphology with the morphology of the common ancestor proposed by this methodology.” In any case, Gomez-Olivency believes it is a “very fine work to reflect the morphology of the teeth” and “very good research”.

They have not found the last common ancestor of Neanderthal and modern man, but have fulfilled the other fundamental objective of research: “We wanted to establish a methodological framework for the analysis of other fossil footprints and I want to emphasize that the programs and data we have used are available for the use of those who want,” said Gómez Robles. In fact, requests have already been received so that the new candidates for a common ancestor are analyzed using this methodology.

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia