Sex, a variable forgotten by science

2017/09/01 Labaka Etxeberria, Ainitze - ErizainaErizaintza II saileko irakasle eta ikertzailea EHU Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

Yentl syndrome is not a real syndrome, but a serious phenomenon. Dr. Bernadine Healy, entitled The Yentl Syndrome, reported that women with cardiovascular disease often received inadequate diagnoses and treatments. In homage to the protagonist of a film, he named Yentl the syndrome. In the film, Yentle wanted to study Talmud, the rules and customs of the Jews. However, being a woman, this school was prohibited and disguised and only by pretending to be a man got the same chance as men.

What does this film have to do with cardiovascular disease? Well, Healy linked to the fact that when women who suffered a heart attack went to the hospital with a previous discomfort, healthcare professionals did not perceive that it was a heart problem or until the heart attack occurred. In fact, those listed in cardiology manuals as typical symptoms of angina in the heart came from studies conducted exclusively with men. But the anatomy of the heart veins is different in people and also symptoms. Therefore, the typical symptoms of women did not always fit the typical clinical criteria, which confused the diagnosis. If any woman expressed the same angina pain as men, on the contrary, they easily diagnosed her with angina of the heart. This is how Healy compares the film to the situation in hospitals. According to him, in both cases, women only acquired a correct treatment when men appeared, in one dressed as men and in the other presented symptoms of being human.

This editorial clarifies the sexual differences of angina of the heart. Angina pain occurs when there is coronary heart failure and, in men, is described as a feeling of chest pain and/or extensible pressure to the arms. Women do not always have angina pain before a heart attack, and in those who suffer it, the characteristics of the pain may be different: chest stings and pain that extends to the neck, scrub, throat, chest or back. Breathing is also common in both sexes.

However, Yentl syndrome is still alive and some say they are in full form. Since the incidence of heart attacks is higher in men, it is still considered as a male disease by forgetting that it is the main cause of death in both sexes. Due to these phenomena and deficiencies, the prognosis of women with heart failure is weaker today. In fact, diagnostic tests and treatments are not as accurate for women as for men, since preliminary experiments, in general, have been performed with male sex. Why only with males?

Away from Adam's Ribs

A few years ago it was thought that only the cells of the reproductive system differed according to sex, that the rest of the cells and biological systems were identical in both sexes. Thus, it seemed sufficient to conduct experiments with males, since it was known that in females the results were the same. Now we know that every cell has the sex of its owner and that there are many differences beyond the reproductive system. For example, female immune cells will respond more strongly to a bacteria and eliminate it more easily. On the other hand, this great spontaneous immune reaction also has its negative side. Women have more autoimmune diseases such as arthritis and multiple sclerosis, in which defenses attack the body itself. The highest incidence of depression among women is also related to this great immunity, as it is believed that permanent activity of defenses can damage the emotional spaces of the brain. The risk of cancer mortality is 1.6 times higher in men. Although we do not know the cause of the latter, researchers have suggested different antioxidant mechanisms and sexual differences in the immune system and hormones.

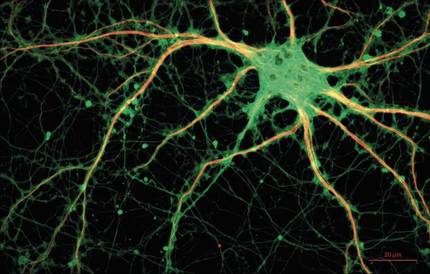

Sexual differences have also been found in in vitro research, i.e. in research with empty cells without using animals. Female neurons, for example, assimilate the messenger that regulates dopamine, pain and pleasure twice as fast as males. In addition, male and female neurons behave differently during the epoch of apoptosis, i.e. during the process of cell death. For stem cells derived from muscles, female stem cells are more persistent and have a greater ability to regenerate skeletal muscle. Moreover, female liver cells have more CYP3A genes. This latter difference is essential, as this gene participates in the metabolization of many of the drugs on the market. In this sense, women have a 50-75% higher risk of exposure to the harmful effects of drugs. In view of the above data it is difficult to understand why no experiments with females are performed. But, as we shall see below, there is a strongly rooted idea in the scientific community that causes females to be excluded from experiments and has to do with the rule.

Females, complicated or unknown?

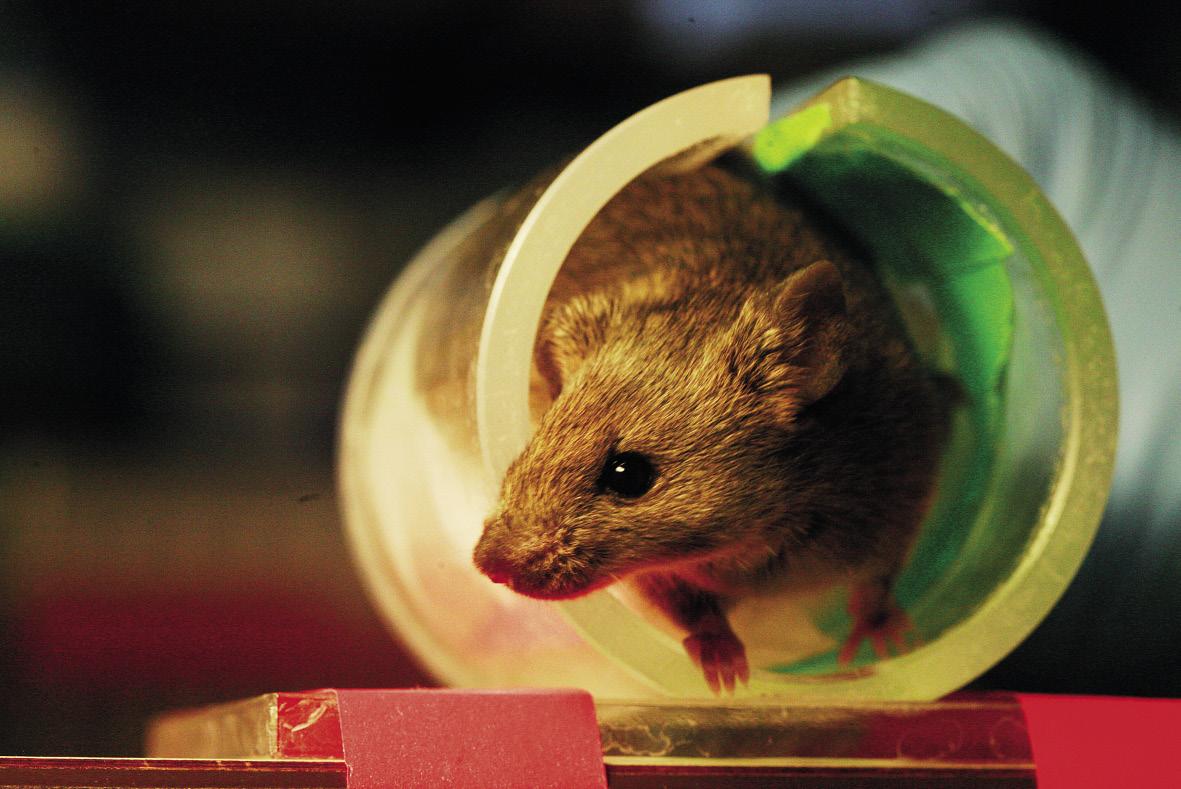

According to some researchers, the incorporation of females in the research would hinder the methodology of the experiments and obtaining solid results, since female mice are more variable. This variability has been attributed to hormonal alterations typical of the estral cycle, equivalent to that of the human rule. In addition to increasing the complexity of the research, it is suggested that the use of the females would make the experiments more expensive, as more hours of work would be needed to determine at which stage of the stral cycle they are at each moment, and that many female mice would have to be bought in order to group them according to the cycle.

However, a gigantic analysis carried out in 2014 in the USA taking into account mice of different races revealed that females are no more variable than males, neither in biological measurements nor in behavior. In other words, the variability that females can have with hormonal fluctuation is not superior to that between them. This latest research has called into question this need to control the pre-critical cycle.

Nevertheless, it is clear that both sexes must be taken into account in order for research to be accurate and exploitable, but the data that reflect actual practice is not very satisfactory. Only 31% of clinical trials for cardiovascular disease research include women and female depression studies do not reach 45%. In addition, according to a study in the biomedical database Medline, of the 443 articles published in 2010 and 2011 only 28% used female mice, and of the 71 articles published in the journal Pain on pain in 2015, 56 did not use females.

The other side of the coin

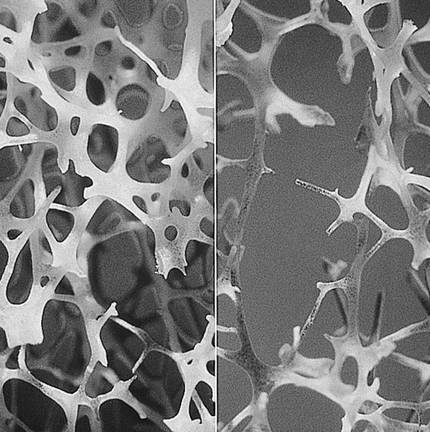

Although the general trend is contrary, there are diseases little studied in pink sex that have greater incidence in women, such as osteoporosis. A person is considered to have osteoporosis when it decreases the consistency of his bones and increases the risk of bone fracture. Much research has been done on women's osteoporosis, since many cases are detected after menopause, but it also affects men. In Europe, one-third of hip fractures related to osteoporosis occur in men, but have little chance of prevention and treatment, as it is considered a postmenopausal disease of women. Primary osteoporosis, the most known, appears with age and, with menopause, is aggravated due to the decrease in estrogens that until then have protected the bones of the woman. In men, androgens have protective function and their decrease is very gradual, so osteoporosis does not appear suddenly in men. Secondary osteoporosis, on the other hand, is more common in men than in women and is related to clinical situations and treatments that can cause bone loss. However, we have little information about male osteoporosis.

Another is breast cancer. Its incidence in men is very low, and practically all studies on the subject have been done with women and female animals. Due to poor knowledge, diagnosis is usually late and treatment is based on women, although it is suggested that the type of tumor may be different in men.

Although it seems paradoxical, there are organizations that have clear the need to distinguish males and females in their research with the aim of equality. The Food and Drug Association (FDA) and the United States Institute of Health (NIH) have regulated the inclusion of both sexes in their research. In addition, the journals Nature and Journal of Neuroscience Research have joined this initiative, among others.

Bibliography

Note

The author would like to thank the predoctoral collaboration of the Basque Government.

Gai honi buruzko eduki gehiago

Elhuyarrek garatutako teknologia