Old news

2006/04/01 Arbelaitz Ubegun, Estibaliz - Biologian lizentziatua Iturria: Elhuyar aldizkaria

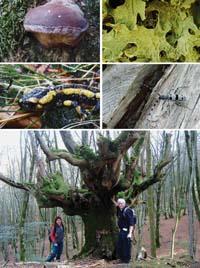

There are trees of these characteristics in the Basque Country, although they are not of many years, and many of them were embedded in an era: they are called transmochos or short trees. These trees are the result of the history of our forests.

Trees, historical imprint

Until the Middle Ages forestry was not so important in the Basque Country, but in the XIII. From the 20th century the demand for wood began to increase, especially for use in construction, steel and the naval industry. Over time, and especially because of the importance of steel and shipbuilding, forests began to be harshly exploited. The trees were cut by the limit of the earth and, as in some years new shoots were formed, they obtained usable wood: they were called charadis.

The main problem of this form of management was the construction of fences in the area to prevent new outbreaks from being eaten, which provoked numerous clashes between those who intended to exploit wood and promote livestock. As a result, a new way of managing trees emerged: shallow or short trees. They were cut at a height of 2-3 m and as the new shoots developed above that height, the farmers could leave the animals on the mountain and at the same time exploit the wood. In this way there was a solution to many actions, so the management of the trees extended to many villages. Therefore, in our mountains we can enjoy numerous forests of short or misty trees.

Why are they important?

Just as ancient figures and buildings are protected, why should not these ancient trees also be protected? They are remnants of history and the last remains of a life that is about to be lost. The trees located in the lower valleys were used for the naval industry and those that were far away to form charcoal: the producers of short-lived trees that we can find in our high mountains were chargers. On the mountain they spent days and days taking care of the txondorra. Today, without this activity, these types of trees are in danger of extinction, both due to the loss of the old and the absence of new ones. But besides being the last vestiges of this way of life, these trees are also areas of high ecological value.

The rot process is initiated by fungi and some invertebrates also help. It thus becomes the beginning of a long chain. Throughout this process a wide variety of microhabitats are generated in which numerous living beings such as fungi, invertebrates and associated birds coexist. The holes that are created are used by animals to spend the winter or summer (for example, lirones) and to hunt (for example, spiders). The base of this type of chain are the old trees, which being a habitat protects the associated flora and fauna. In Sweden, for example, they protect a surface of 3 ha, protect 400 species from the Red List.

On the other hand, the dead wood rots and becomes organic matter, so the tree "recycles" and, to return to the tree, develops roots from the top of the trunk down.

How to manage these trees?

The main problems that can be observed when managing these trees are their high and high canopy, and in some cases the competition of young trees and soil compaction. Unmasked ancient people develop large branches that lose balance. Therefore, an intense wind or rain can knock down trees or break branches. The only way to deal with this problem is to retake the tree, with the aim of bringing the center of gravity down, so it is necessary to gradually reduce the top to bottom cup, again around the trunk to get the balance. These short ones depend on the state of the tree, and once the balance is achieved it is necessary to continue with the costume.

Before starting with the reduction of the cup you have to observe what is around the tree to work. In our mountains, there are often numerous shaded trees, and it is advisable to reduce the cup in groups, since what has been disguised can be without light.

In some cases, the problem is the young plants that are around. Being old trees, they are very sensitive to the competition that neighbors can do and lack of light can kill them easily. In these cases all the young plants surrounding the old tree are eliminated by a kind of ring. However, this is a work to be done gradually, since the solar rays can burn the surface of the tree. To avoid this, a gradual cleaning of the area (making a few small rings around the tree) from the outside to the tree.

The root system of these trees is also very sensitive and the excessive compression of the soil can kill the tree. Therefore, the root system must be protected by placing enclosures or placing obstacles around the tree.

New generations of old trees

As already mentioned, old trees are the habitat of a large number of cultural heritage and threatened species that, to maintain their populations, need other trees with characteristics typical of old trees. In addition, many of these species are not able to travel long roads, so that the population continues to need adequate habitats for them. It has been seen that the quickest way to achieve this is the network of young tree plants, and for this, like the chargers did, we have to follow a series of steps: first we have to necklace the young tree and then introduce it in a cycle of disguise.

However, until the young transmochated trees become suitable for these species, they will spend many years and, to overcome this intergenerational leap, we should try to keep alive the old existing trees.

Distribution of old trees in Europe and Euskal Herria

However, high density areas of old trees are more important than isolated trees, always from the animal and plant point of view in danger. The abundance of trees guarantees the existence of numerous corners, microorganisms that need specific microhabitats are more likely to develop more sustainable populations, a group of trees gives greater protection from changes than an isolated and a group of trees provide more information about the past than a single tree.

Therefore, we have the opportunity to look with other eyes at these groups of old trees that we have in Euskal Herria. Having such a high density allows us to learn by testing in many European countries.

Thank you, Iñaki and Arturo, for allowing us to enter this world.